A mind-numbing study published in early February has made headlines around the world: The average human brain now contains approximately seven grams of microplastics. According to the researchers, that’s about the same weight as a throw-away plastic spoon.

The research was conducted at the University of New Mexico and was published in Nature Medicine. The researchers conducted autopsies on cadavers from 2016 and 2024 and found during that eight-year period the amount of microplastic fragments found in brains has increased by about 50 percent

However, though this particular study made colorful headlines due to the researchers’ clever comparison to the weight of a plastic spoon, it is certainly not the first study highlighting the dangers of microplastics.

Microplastics background

In fact, microplastics have been a growing concern for over two decades.

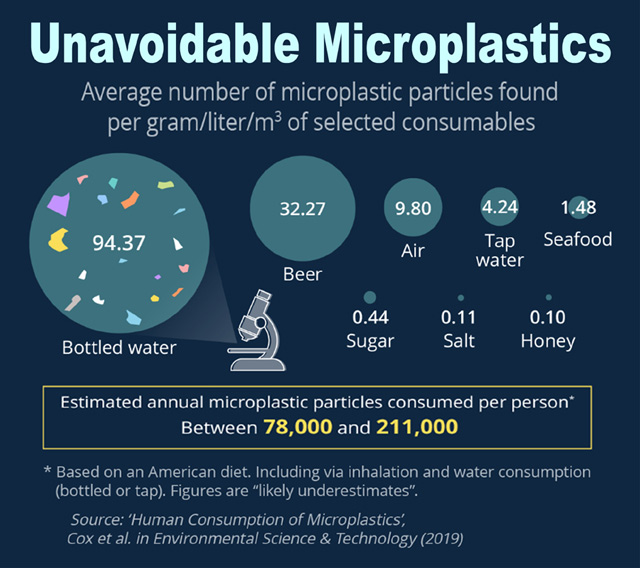

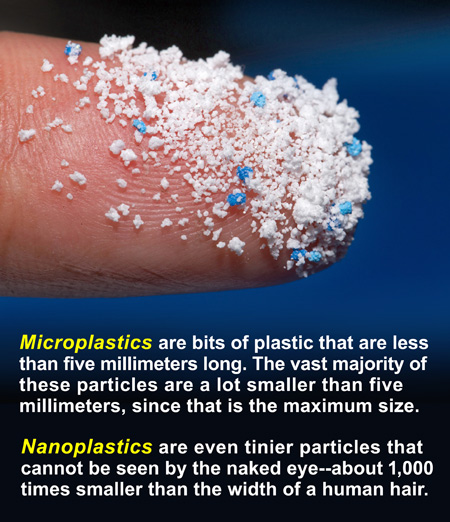

The term “microplastic” was first used to describe minscule fragments of plastic debris in a scientific publication in 2004. Since that time most research has focused more on the amount of microplastic accumulation, and less on proving a link to various health issues.

A 2024 article published in Science lamented this fact. While noting that microplastics were “pervasive in the food we eat, the water we drink, and the air we breathe,” the authors of the paper pointed out that the evidence of adverse health effects was “barely emerging.”

Further, while agreeing that numerous studies had proven the presence of microplastics “in multiple tissues and organs” of the human body, they still felt that “risk assessments are limited because exposure and effect data are incomplete. “

But this view may be about to receive a drastic update as new studies appear to make the dangers abundantly obvious.

Recent studies

For example, a study published in March 2024 found that people with higher concentrations of microplastics in their arteries were at a higher risk of heart attacks, stroke and death. The study involved a three-year follow-up, and, according to the researchers, it was the first scientific study providing “direct evidence” of microplastic health dangers.

In another new study, presented in January 2025 at the annual meeting of the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, scientists unveiled research that found both microplastics and nanoplastics occurred in higher concentrations in the placenta of infants born prematurely compared to those born at term.

While this discovery may seem counter-intuitive at first, according to the researchers it is highly suggestive that the accumulation of plastics could be contributing to the risk and occurrence of preterm birth.

Put another way, pregnant women who already have a high accumulation of microplastics are much more likely to suffer an early delivery of their babies.

Another January 2025 study, published in Nature, found microplastics block blood flow in the brains of mice. Researchers involved in the study used real-time imaging to show how “plastic-stuffed cells” formed clumps that affected neurological function and the normal movements made by the mice.

While mice are not humans, they are frequently used for preliminary studies because mice experience many of the same diseases as humans and have the same types of organs and bodily systems.

In addition, around 95% of the genes that code for proteins are identical in humans and mice—making them excellent models for human disease.

For this reason the findings are considered highly indicative of how microplastics are also penetrating the brains of humans and contributing to neurological problems.

This assumption would seem to be corroborated by the “teaspoon of plastic” study that was published the following month.

Dementia link?

As already mentioned, the teaspoon study grabbed attention worldwide with the imagery it induced. Picturing a spoon-sized amount of microplastic in one’s brain is sure to do that. But it was the link to dementia that was the real news.

In addition to learning that the amount of microplastics in the average human brain had increased to the weight of a spoon, the researchers also found microplastic concentrations were higher in the brains of deceased patients who had been diagnosed with dementia—suggesting that microplastics do, indeed, cause neurological problems.

It is important to note the study only establishes a correlation between high levels of microplastics in the brain and dementia. It does not prove a causal relationship. However, the correlation carries more weight when considered in conjunction with the other studies. This includes the mouse study published only a month earlier that demonstrated microplastics induced neurological impairment.

If the dangers or microplastics have not yet been proven “beyond all reasonable doubt,” they are, at the minimum, at the level of “preponderance of guilt.”

Mitigating risk

Considering how long it took to definitively prove the dangers of pesticides, herbicides and fluoride, we could be decades away from the “proof” becoming widely accepted. In the meantime, a reasonable person should conclude that there is already enough evidence to take steps to mitigate the damage caused by the plastic world we live in.

Mitigation efforts include avoiding plastic for cooking and storage, filtering water, and taking nutritional supplements that can help eliminate microplastics from the body.

For example, Optimal Chemzyme from Optimal Health Systems provides a potent formula developed to address the alarming increase in food additives and harmful chemicals found in the modern diet.

A unique enzyme known as Phthalazyme is a critical part of this formula since it is the first and only enzyme specifically designed to digest and detoxify the phthalates found in plastics.

Learn more about Phthalazyme in our previous post here.

– – –

Sources:

•Nature Medicine (2025 plastic in brain “spoon-size” study).

•New England Journal of Medicine (2024 heart/stroke study).

•SMFM.org (2025 premature birth study).

•Nature.com (2025 mouse neurological study).