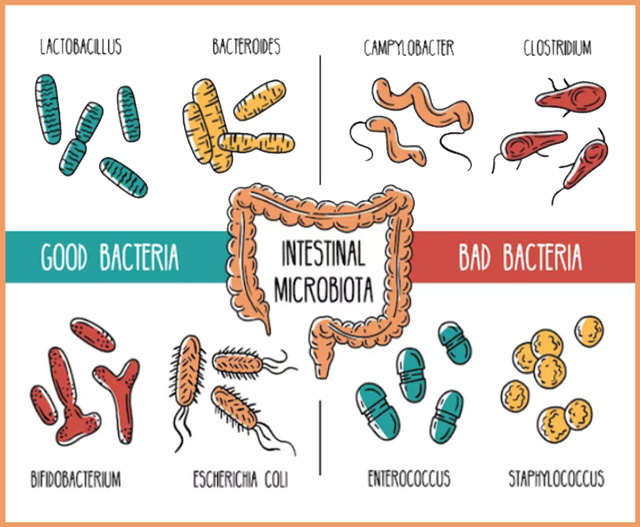

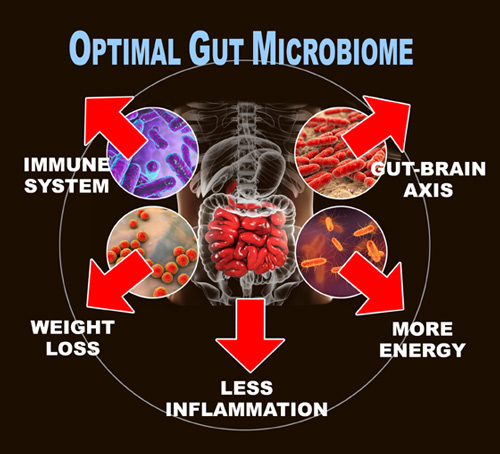

Almost everyone who is interested in maintaining an healthy immune system knows the first critical step is to optimize the gut. Afterall, an estimated 70 percent of a person’s immune system lies within the gut.

People who connect the dots even further realize that the optimized immune system is related to reduced inflammation in the body overall.

In the latest discovery by Harvard Medical School, researchers have learned that the immune/anti-inflammatory benefit of an healthy gut extends to faster healing of muscle injuries.

The researchers, conducting a study on mice, found healthy gut microbes were better able to “fuel” the immune system’s T cells when compared to unhealthy guts. T cells are a type of white blood cell that help protect the body from invasive bacteria and infection.

Researchers found that healthy gut bacteria powers specific cells called “regulatory T cells”—abbreviated as “Tregs.” Tregs are highly specialized. They reside in various organs, where they control local inflammation and regulate organ-specific immunity.

Put another way, the main function of Tregs is to go around the body and respond to inflammation at injury sites in order to heal them.

“Our observations indicate that gut microbes drive the production of a class of regulatory T cells that are constantly exiting the gut and act as sentries that sense damage at distant sites in the body and then act as emissaries to repair that damage,” wrote researchers from the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School in a university release.

The researchers also noted that though it is well-understood that healthy or “friendly” gut microbes play a critical role gut immunity through Treg production, so far there has been minimal research into what Tregs do to tissues outside of the gut.

Optimal gut microbes lead to less scars after an injury

To answer the question of why these cells would work outside the gut, the researchers setup a testing system using animal models.

First researchers had to make sure that the Tregs found within the muscle tissue were actually from the gut. The scientists analyzed the molecular structure and confirmed their identity. They then tagged the Tregs with light and followed them as they moved around the bodies of mice. They found that the cells left the gut lining and moved to other parts of the body.

“The immune cells we had found in the muscle shared the same barcodes with the equivalent Treg cells in the gut,” the researchers wrote.

While monitoring the healing process, the team found that genetically modified mice lacking these Tregs had slower muscle recovery than those who had them. They examined this more closely and found that these mice had more inflammation at the injury site. Even once they did heal, they had scarring or fibrosis—showing that the muscle didn’t heal well.

To see if gut bacteria played a role in this, the team fed mice antibiotics to kill their beneficial gut bacteria. They found that these mice also had a difficult time with muscle repair. Once their gut flora was back to normal, they were able to heal better.

“It is well known that antibiotics can eradicate beneficial gut microbes as collateral damage of their main function, which is to kill harmful bacteria,” researchers wrote in the study summary. “Our results further underscore the importance of judicious antibiotic use, which is important for many reasons that go well beyond muscle recovery.”

Additional benefit: organ protection

To determine other benefits of Tregs in the body, the researchers followed them throughout the body. They looked for traces of gut Tregs in various organs such as the liver, kidneys, and spleen. These critical organs also contain intestinal Tregs, but in smaller amounts.

To conduct this final experiment, the team induced fatty liver disease in a group of mice. Fatty liver disease usually results in liver scarring, cell death, and organ damage.

The researchers discovered that mice with fatty livers had higher levels of gut Tregs than those with healthy livers. Recalling that Tregs are “regulating” cells—and power up to support an injury—the higher level of Tregs in the fatty liver mice showed that the Tregs can regulate inflammation in places besides the gut.

The researchers noted that the findings open up new possibilities for disease treatment in the future. They posited that using probiotics to restore a healthy microbiome will not only be used for digestive issues, but for healing external injuries and fatty livers.

The findings are published in the journal Immunity in February 2023. The researchers cautioned that the study was conducted on mice, and noted further human studies are needed; however, the results add to the growing body of evidence showing how important the gut microbiota is in regulating various physiologic functions beyond the gut.

Optimal Health Systems has been promoting the critical benefits or beneficial bacteria (probiotics) for over two decades. For this reason many probiotic blends are included in the Optimal Health Systems product line. Click links below to learn more.

• Flora Blitz 100

• Optimal Flora Plus

• 21-Day Blitz Challenge Package

• Exposure Protection Pak

• Natural Z Pak

• Optimal Defense

– – –

Sources: Immunity, Harvard Medical School-News & Research.