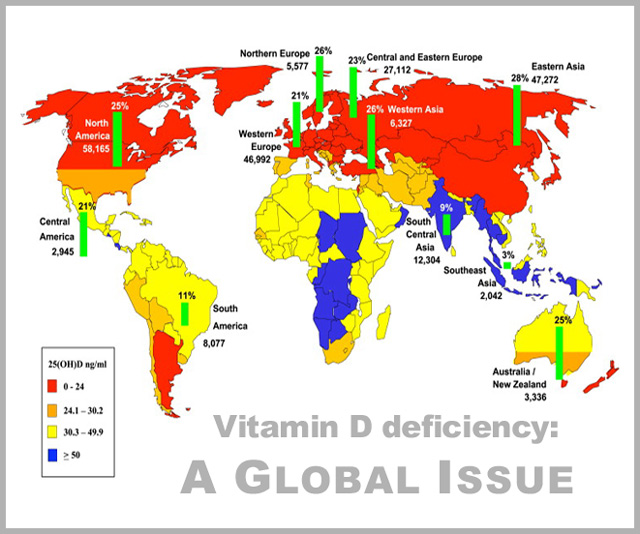

Repeated studies have shown that Vitamin D deficiency is a global health problem—and, according to a 2018 study, the U.S. is definitely one of the deficient nations.

Now the bad news: it’s going to get worse.

According to a new simulation study from the Netherlands, adequate Vitamin D intake cannot be achieved within the carbon emission limits that are currently being followed in the European Union.

Similar limits are being proposed in the U.S. at the federal level, and are already enacted in many states.

How Vitamin D intake conflicts with carbon reduction

Because traditional high Vitamin D foods—such as meat and diary—are curtailed under carbon reduction laws, it will be necessary to expand Vitamin D fortification of other foods, say the researchers.

The problem with this plan, according to many nutritional advocates, is that the nutrients used to fortify foods are inevitably the cheap synthetic versions that bare little resemblance to real foods or whole food vitamins and minerals.

Synthetics typically do not absorb well, and they often do not contain the nutrient co-factors available in whole foods.

The study, published in the journal Nutrients in December 2020, was sponsored by a Swiss nutritional products company and was based on a Dutch “model diet.”

Other sources of Vitamin D

It should be noted that food is only one source of Vitamin D. In fact, food provides a relatively small proportion of the Vitamin D supply, while Vitamin D produced in the skin from UVB light makes the greatest contribution. However, changing demographics, how people spend their time, and even current pandemics, make it difficult to achieve adequate exposures.

For this reason people have become more dependent on foods and supplements in recent years—especially in colder countries with long winters.

Now an even bigger dilemma is on the horizon as politicians try to force a switch to carbon friendly practices:

“Only few foods naturally contain significant amounts of Vitamin D and they are mainly animal derived—oily fish, meat, dairy and eggs—so shifting to more plant-based diets is likely to further aggravate the risk of deficiency,” said the authors of the study.

Study details

This study applied linear programming to simulate the dietary shifts needed in order to optimize the intake of Vitamin D while attempting to minimize the carbon footprint.

Scenarios were modeled with and without additional fortified bread, milk and oil as options in the diets. The baseline diet provided about one-fifth of the adequate intake of Vitamin D from natural food sources and voluntary Vitamin D-fortified foods.

Nevertheless, when optimizing this diet for Vitamin D, the food sources together were insufficient to meet the adequate intake required. The only way to change this was for the carbon emission and calorie intake to be increased almost 3-fold (without fortified food included) and 2-fold (with fortified food).

“The modelling study shows that it is impossible to obtain adequate Vitamin D through realistic dietary shifts alone, unless more Vitamin D-fortified foods are a necessary part of the diet,” said the researchers.

In short, the researchers assume it will be impossible to convince the masses to trade in their favorite foods in exchange for a bucketful of carbon-friendly mushrooms each day; hence, consumers can expect to start seeing a big expansion in “fortified” foods.

If you’d rather skip the packaged and processed food—even if they are “fortified” with synthetic vitamins and minerals—consider the whole food option instead. Learn more by watching the videos included at the bottom of this article.

For more information on different Optimal Health Systems products with Vitamin D, check out the following product pages:

• Essential DAK1K2

• Exposure Protection Pak

• Optimal Whole Food Vitamin-Mineral

• Optimal Longevi-D

• Opti-Immune-VRL

– – –

Sources: Journal Nutrients / MDPI Database